Authenticating Lapis Lazuli: Formation, Testing & Quality

Lapis lazuli has a long history and its valued not only for its deep blue colour but also for its cultural and spiritual significance. In ancient Mesopotamia, it was seen as a stone of the gods, used in seals and amulets to symbolise power and provide protection.

The ancient Egyptians admired it just as much, incorporating it into jewellery, scarabs, and even the iconic burial mask of Tutankhamun. They believed it held protective and guiding qualities, helping souls transition to the afterlife. Cleopatra is said to have crushed lapis into powder for her distinctive blue eye makeup.

In Greece and Rome, lapis was used to craft intricate carvings, signet rings, and other symbols of wealth and status.

By the Renaissance, it became even more valuable as artists ground it into ultramarine, one of the most expensive pigments of its time. It graced the works of masters like Vermeer and Michelangelo, reserved for only the most significant details.

Lapis lazuli’s symbolism has been just as enduring as its physical beauty. Known as the “Stone of Heaven” in some cultures, it was thought to inspire wisdom, clarity, and connection to the divine. Its name reflects its legacy—"lapis" means "stone" in Latin, while "lazuli" comes from the Persian lajward, meaning "blue". Over time, the stone has gained many nicknames, but none as authentic as the legacy it carries.

Geography & Geological Formation of Lapis Lazuli

Lapis lazuli is primarily found in specific regions known for their unique geological conditions, with Afghanistan being the most famous source. The deposits in the Sar-e-Sang mines of the Badakhshan province have been mined for over 6,000 years, producing some of the highest-quality lapis lazuli in the world. These mines are located in a remote mountainous region, where metamorphic conditions provided the perfect environment for the formation of this iconic rock.

Lapis lazuli forms in limestone through a process of contact metamorphism. This occurs when molten magma interacts with limestone, causing chemical and mineralogical changes due to intense heat and pressure. The result is a rock composed of lazurite, calcite, pyrite, and other trace minerals. The presence of lazurite gives lapis its blue colour, while pyrite adds its characteristic golden flecks, and calcite appears as white streaks or patches.

Outside of Afghanistan, lapis lazuli deposits are found in other parts of the world, though these typically yield stones of varying quality. Notable sources include Chile, which produces material with a lighter, more uniform blue, and Russia, where deposits in the Lake Baikal region offer stones with a more muted tone. Additional sources include Pakistan, Myanmar, and smaller deposits in the United States and Canada, though these are less significant in the global market.

The quality of lapis lazuli depends on the proportion of lazurite to other minerals. Stones with a high concentration of lazurite and minimal calcite are considered premium quality, while those with more calcite or uneven colouration are less desirable. Geological conditions at each deposit directly influence these characteristics, making Afghan lapis renowned for its rich colour and minimal impurities.

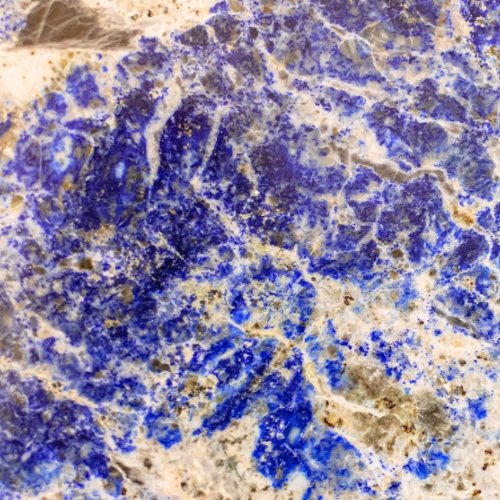

Image: Natural lapis lazuli freeform.

Ethical concerns Mining Lapis Lazuli

Afghanistan's lapis lazuli mines, particularly in the Badakhshan province, have long been a significant source of this prized blue stone. However, the control of these mines has been linked to funding armed groups, including the Taliban. Reports indicate that such groups have earned substantial revenues from the extraction and trade of lapis lazuli, contributing to ongoing conflict and instability in the region.

The Taliban's involvement in the mining sector has raised ethical concerns for consumers and businesses. Purchasing lapis lazuli sourced from conflict-affected areas may inadvertently finance armed groups and perpetuate human rights abuses. This situation has led to calls for lapis lazuli to be classified as a conflict mineral, which would necessitate stricter regulations and transparency in its sourcing.

To address these ethical issues, it is crucial for consumers and businesses to ensure that their lapis lazuli is sourced responsibly. This involves verifying the supply chain to confirm that the stones are not funding conflict or associated with human rights violations. Engaging with reputable dealers who provide transparent sourcing information and support ethical mining practices can help mitigate these concerns.

While Afghanistan remains a major source of high-quality lapis lazuli, the ethical implications of its extraction under current conditions necessitate careful consideration. Responsible sourcing is essential to avoid contributing to conflict financing and to promote sustainable and ethical practices within the gemstone industry.

Chemical Composition & Colouring

Lapis lazuli is a rock, meaning it is composed of multiple minerals rather than being a single mineral like quartz or diamond. This means that it’s also not crystalline or considered a crystal.

Its characteristic deep blue colour is primarily due to lazurite (Na₃Ca(Si₃Al₃)O₁₂S), the dominant mineral in its composition. Lazurite’s blue hue comes from sulphur trapped within its crystal structure, which interacts with light to create the vibrant ultramarine colour associated with high-quality lapis lazuli.

Pyrite (FeS₂) is another key component, visible as metallic golden flecks. These inclusions are a hallmark of natural, authentic lapis lazuli. Calcite (CaCO₃), often seen as white streaks or patches, is also present and can influence the stone’s overall appearance.

Rocks with a higher lazurite content and minimal calcite are generally considered more desirable, as excessive calcite can lighten the colour or make the stone appear uneven.

In addition to these primary components, lapis lazuli may contain trace amounts of other minerals, such as diopside, feldspar, and mica, which subtly affect its texture and appearance. The unique combination of these minerals gives each piece of lapis lazuli its distinctive character.

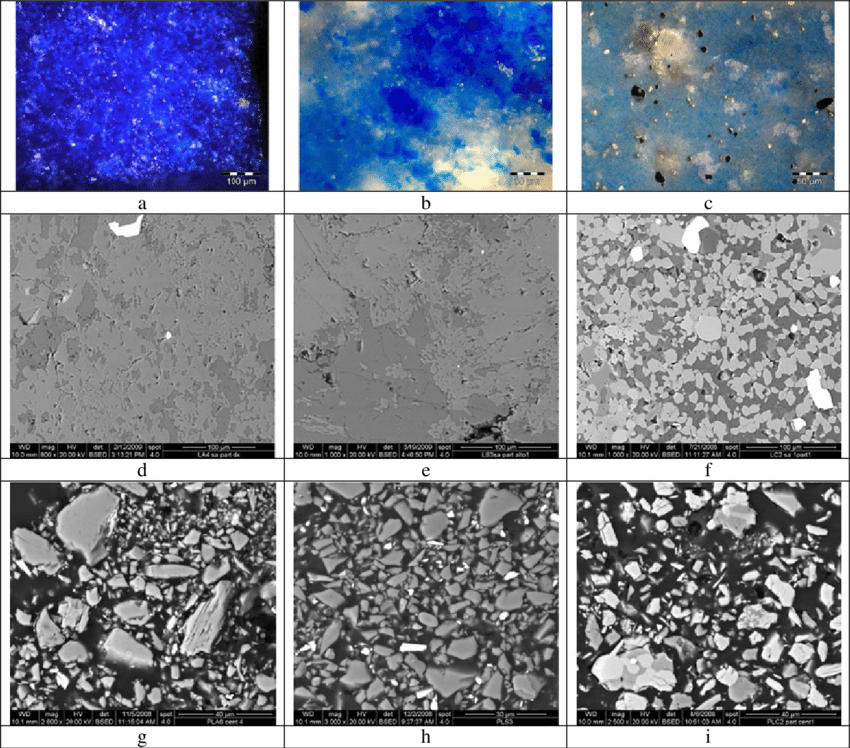

Below shows the differences between lapis from Afghanistan, Russia and Chile.

a-i Optical microscopy (first row) and FEG-ESEM (second and third rows) images of the Afghan (a, d, g), Siberian (b, e, h), and Chilean (c, f, i) lapis lazuli stones and their derived pigments (third row)

Identification Of Lapis Lazuli

SUGGESTED TESTING METHODS

We recommend using the following standard gemmological tools and methods to determine authenticity:

OBSERVATION

Lapis lazuli is typically a rich blue colour, ranging from medium to deep shades, often with a slightly mottled appearance due to its composite nature as a rock. Its polished surfaces exhibit a dull to slightly vitreous lustre. One of its most distinctive features is the presence of golden pyrite flecks scattered throughout, which resemble tiny stars against the blue background. White streaks or patches of calcite are also common, adding to its visual texture. Lapis lazuli is generally opaque, but in rare cases, it may appear slightly translucent in very thin sections or around the edges when held against strong light. These natural variations make each piece unique.

LOUPE (OR MICROSCOPE)

Under magnification, lapis lazuli reveals a wealth of clues to its identity. Examine the surface for its unique combination of minerals. Look for the golden flecks of pyrite, which are irregularly distributed but often appear as tiny metallic particles embedded in the blue matrix. White calcite streaks or patches may also be visible, creating areas of contrast against the lazurite-dominant sections.

The texture of lapis lazuli is typically uneven, reflecting its nature as a rock composed of multiple minerals. In unpolished areas, you may notice a slightly granular or crystalline structure, with the lazurite portions appearing smoother and more homogenous compared to the calcite or pyrite inclusions. These visual and textural characteristics can help distinguish natural lapis lazuli from imitations, which often lack the natural variation and detail seen under magnification.

SPECIFIC GRAVITY

Specific gravity (SG), or relative density, is a useful diagnostic property for identifying lapis lazuli. As a composite rock, the SG of lapis lazuli typically falls within the range of 2.7 to 2.9, depending on its mineral composition. Lazurite, the primary component, contributes significantly to this density, while variations in the amounts of pyrite and calcite can cause slight deviations.

To measure SG, a hydrostatic balance can be used. If the specific gravity falls within the expected range, it supports the identification of the material as lapis lazuli. Values outside this range could indicate an imitation, such as dyed howlite (which has a lower SG), or a composite material with a differing density. This test is particularly helpful in confirming the authenticity of the stone when combined with other visual and physical characteristics.

Close-up: Golden pyrite flecks

Lapis Lazuli or Sodalite?

Struggling to tell the difference between sodalite and lapis lazuli?

Lapis Lazuli Gallery

similar materials, misnomers & synonyms

SIMILAR MATERIALS

Sodalite: Often confused with lapis lazuli due to its deep blue colour, sodalite lacks the golden pyrite flecks and typically has a lighter, more uniform blue.

Azurite: This mineral shares a similar vivid blue but tends to have a more crystalline appearance and no pyrite inclusions.

Blue Calcite: While it can mimic the colour of lower-grade lapis, it is much softer and often lacks the signature pyrite inclusions.

Dyed Howlite or Magnesite: These are common imitations of lapis lazuli, as they can be dyed to a similar blue shade but lack the natural patterns and golden flecks of pyrite.

SYNONYMS

The Stone of Heaven: A historical nickname from ancient cultures that associated lapis lazuli with divinity and celestial realms.

Ultramarine Stone: Refers to its historic use in creating ultramarine pigment for art.

Lajward: The Persian word for “blue” which inspired the name lazuli and was used historically to describe the stone.

MISNOMERS

Swiss Lapis: A trade name for dyed jasper or quartz, often sold as a lapis lazuli substitute despite being a completely different material.

German Lapis: Another misnomer for a dyed or imitation material, commonly used to market lower-value substitutes.

Armenian Stone: Occasionally used in older texts to refer to lapis lazuli, though this term lacks geological accuracy and regional connection.

Enhancements & Artificial Materials

TREATMENTS

Lapis lazuli is often untreated, with its natural deep blue colour and golden pyrite inclusions.

Dyeing: Lower-quality lapis is sometimes dyed to enhance its blue hue or improve its market appeal. Dyed lapis often exhibits an unnaturally uniform colour and may lack the natural variations seen in untreated stones. Such treatments can usually be identified under magnification or through tests like acetone application, which may remove or alter the dye.

Waxing or oiling is another common treatment applied to lapis lazuli to improve its surface lustre and appearance. These enhancements are typically less intrusive than dyeing but can still affect the stone's value. Awareness of such treatments is important when purchasing lapis to ensure clarity on the stone’s condition and authenticity.

IMITATIONS

Sodalite: Sometimes sold as an imitation but lacks the golden flecks of pyrite. In some cases, composite stones made of crushed lapis lazuli mixed with resin are sold as “reconstituted lapis”, offering a lower-cost alternative that is not entirely natural. As always, purchasing from a reputable dealer is essential to ensure authenticity.

Nano Sital Lapis: is a lab-created material designed to replicate the appearance of natural lapis lazuli. Composed primarily of silica (SiO₂) and alumina (Al₂O₃), it mimics the deep blue colour of natural lapis but may lack the signature pyrite flecks and calcite inclusions. Artificial lapis should always be clearly disclosed to buyers to ensure transparency.

RECONSTRUCTED MATERIALS

Reconstructed Lapis Lazuli: is a manufactured material made by crushing natural lapis fragments, mixing them with resins or dyes, and forming them into blocks or shapes. While it mimics the blue colour and pyrite flecks of natural lapis, its appearance can be overly uniform, and it is softer (Mohs 3–4) due to the resin content. It is more affordable and often used in cost-effective jewellery and decorative pieces. Reconstructed lapis should always be clearly disclosed to buyers to ensure transparency.

Lapis Lazuli buying guide

HIGHER QUALITY

Lustre: When polished, vitreous and smooth, reflecting light well. When rough, smooth surface with a slightly waxy or matte lustre.

Colour: Deep, rich blue with vibrant ultramarine hues. Even colour distribution across the stone.

Inclusions Minimal white calcite inclusions. Subtle, evenly distributed pyrite flecks.

Condition: Shows no signs of surface scratches or wear, indicating proper handling and care.

LOWER QUALITY

Lustre: Dull or lacklustre, with poor surface polish that diminishes light reflection. When rough, pitted, or dull. Overly shiny surfaces may indicate treatments.

Colour: Pale, greyish, or uneven blue tones. Blotchy or uneven colour distribution.

Inclusions: Prominent white calcite streaks or patches. Excessive or sparse pyrite inclusions.

Condition: Chips, cracks, or surface scratches; large, visible inclusions that affect the overall appearance.